Rafael Alberti: A Biographical Sketch

by Carolyn L. Tipton

Rafael Alberti and the twentieth century progressed along together: born in its infancy, he experienced the excitement and novelty of all the artistic movements of the 1920s in his youth–Cubism, Cinematic Imagism, Surrealism; participated as an adult in the political upheaval of the 1930s, working ardently for a more equitable society; and then, having suffered war and exile, finally reached a place of quiet at the end of the 1940s, a place of maturity out of which he created–and would continue to create for years to come–with insight and a profound nostalgia for the world of his youth.

Early life and the Generation of ’27

Rafael Alberti was born in 1902 in the south of Spain, in the village of Puerto de Santa María on the Bay of Cádiz, along whose shores he spent most of the hours of what he calls his “saltwork childhood”.

During the year he turned fifteen, he moved with his family to Madrid. The longing he felt then for the sea (mitigated only by his discovery of the Prado Museum, in front of whose works he taught himself to paint) eventually came to inform the poems of his first collection, Marinero en tierra (Sailor on Land), a group of thematically linked poems inspired by traditional Spanish folksongs and the Golden Age poets’ sophisticated variations upon them. This work is notable both for its musicality and its evocative imagery, and it won for Alberti, then only 23, the National Prize for Literature (at that time in Spain, the most prestigious literary prize, one of whose judges was Antonio Machado).

Alberti soon was drawn into the circle of poets who came to be known as the Generation of ‘27. This group, which included Federico García Lorca, Pedro Salinas, Jorge Guillén, Luis Cernuda, and Vicente Aleixandre, among others, and who often gathered together in the cafes of Madrid, brought about a literary renaissance there in the 1920s. Alberti published both poems (experimental as well as classical) and essays during these ebullient times.

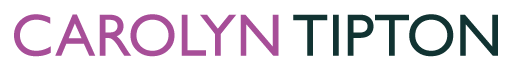

Poets and artists of the famed Generation of Twenty-seven. Rafael Alberti is fourth from right.

Poets and artists of the famed Generation of Twenty-seven. Rafael Alberti is fourth from right.

Toward the end of the decade, however, Alberti’s vision of the world began to darken. In 1929, the same year in which Lorca published Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York), and in which Pablo Neruda, far away in Java, was working on Residencia en la tierra (Residence on Earth), Alberti wrote Sobre los ángeles (Concerning the Angels); all three works are informed by a dark Surrealism. Suffering the sense of a paradise lost, depressed and confused, Alberti nevertheless, as was his way, created a brilliantly unified and organized work. Sobre los ángeles is populated by a tribe of angels, each of whom symbolizes something in Alberti’s inner or outer world, and to each of whom he has given a voice. The angels, Albert would later say, gave shape to the tangle in which he struggled.

Poet in the street

Alberti eventually found his way out of the maze not only through the struggles of his art but also through a confluence of events both romantic and political. He met and soon married the writer María Teresa León, and he became politically involved, demonstrating in Madrid against the abuses of the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera, and becoming a “poet in the street”, tacking up poems on walls and reciting them at rallies.

In 1931, a republic was created, and in 1936, the Popular Front—a coalition advocating land, educational, military and economic reform—was voted into power. General Francisco Franco’s Fascists rose up against the government that July.

During the Civil War that followed, Alberti was very active in the republic’s defense. He served as secretary of the Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals and organized the Second International Congress of Writers to help publicize Spain’s predicament, traveling to Paris and Moscow to invite the delegates, who included Stephen Spender, Langston Hughes, Nicolas Guillén, and Octavio Paz. During this period he served as director of the Museo Romántico, an annex of the Prado, and was responsible for securing it against attack. He also put out a magazine which published most of the important writing of the time and presented both short theatrical pieces and poetry readings at the Front.

Exile: The wandering years

Ultimately, however, the war was lost. With the aid of Mussolini and Hitler, the Spanish Fascist forces crushed the Republicans and, by March of 1939, Spain had fallen to Franco. Many of Alberti’s Generation had been caught or killed, and now Alberti fled for his life. Thus began an exile which was to last almost forty years. He and his wife lived briefly in Paris, but within a month, World War II had begun, and facing the threat of German troops, they escaped on a boat bound for Buenos Aires.Warmly welcomed there, they decided to stay.

The title of his first work written there, Entre el clavel y la espada (Between the Carnation and the Sword) describes Alberti’s existential state. Alberti’s anger and heavy sense of loss became temporized in time, and he gradually began to write less under the sign of the sword and more under the sign of the carnation, incorporating into his work once more a celebration of beauty, a desire for hope and renewal. He never ceased, though, to think of himself first as a citizen of La España Peregrina (Wandering Spain).

For years, he wrote elegies to the Spanish dead, as well as pamphlets about the Spanish refugees and petitions to free the prisoners in Franco’s jails. Even when his poetry began to take up new subjects, it was always deeply informed by his exile. Two of the greatest works of his period of “High Maturity”, A la pintura (To Painting) and Retornos de lo vivo lejano (Returnings: Poems of Love and Distance)—the one an evocation of the world of European painting he had discovered in the Prado, and the other an evocation of the people, places, and emotions of his youth—are often joyous but always rooted in an exile’s sense of loss.

From the late 1950s onwards, Alberti began to travel extensively, not only attending conferences both literary and political, and exhibitions of his paintings, but also giving readings. His writing reflects these changes: he began to write poetic travelogues, to collaborate with both visual artists and musicians (producing both work to be shown, such as his “Homenaje lirico-plastico” (“Lyrical-Plastic Homage”) for the anniversary of Cádiz, as well as work to be performed,for example Invitación a un viaje sonoro, (Invitation to a Sonorous Voyage; a group of lyrics set to musical pieces), and to produce more dramatic pieces and more humorous pieces for his increasingly frequent recitals. The very popular Roma, peligro para caminantes (Rome, Dangerous for Pedestrians) is an example of the latter.

Return to Spain

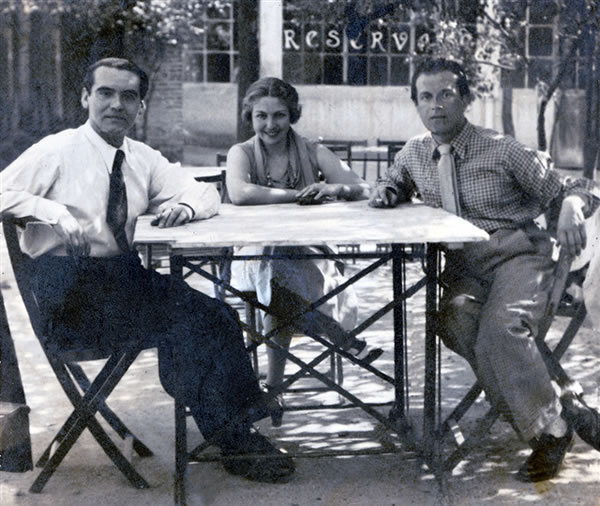

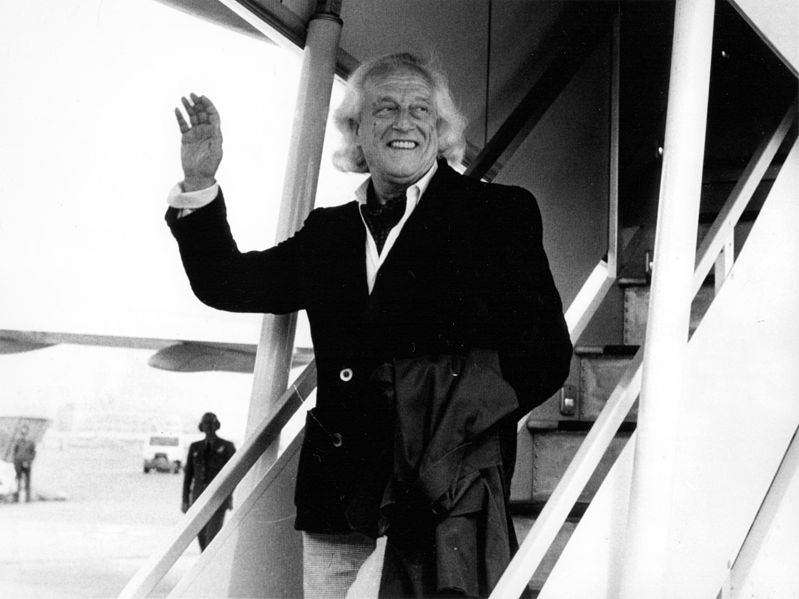

In 1965, Alberti finally returned to Europe to live in Italy, the home of his paternal grandparents, but it was not until 1977, after the death of Franco, and after having received a personal invitation from King Juan Carlos, himself, that Alberti and his wife finally returned to Spain. Hundreds were in the jublilant crowd that greeted them at the airport in Madrid. In the years following the Spanish diaspora, Alberti, more than many others of his Generation, had become a symbol of survival, of resistance, of the unquenchable flame of the artistic spirit.

Finding himself a much revered public figure upon his arrival home, Alberti actively entered into Spanish political and cultural life: he served briefy in the Spanish Cortes (Parliament) as the representative from Cádiz; he appeared constantly at Madrid functions, giving talks and readings; he held local exhibitions of his paintings and “painted poems”; for many years, he even wrote a weekly column in the Madrid newspaper El País.

In the last few decades of the 20th century, Alberti was awarded many prizes and honors, most notably the Premio Cervantes, Spain’s most prestigious literary prize, awarded in 1983 to honor a lifetime of literary achievement. By the time of his death at the century’s close (October,1999), Alberti had published some twenty-four volumes of poetry, produced over seven decades, several plays, some non-fiction prose, and a five-volume autobiography. He remains one of the towering figures of modern Spanish literature.

Carolyn Tipton with Rafael Alberti in Madrid

Alberti Links

Rafael Alberti obituary from The Guardian

Read Alberti poems online: A Media Voz

Blog by Cherry Jeffs: The Twin Creative Passions of Rafael Alberti

Returnings Wins Cliff Becker Translation Prize

Video: A Fondo interview with Rafael Alberti (Spanish)

Blog: La Generación del 27: Spain’s Tragic Literary Generation